By Chandrani Sinha

When cities grow into spaces reserved for rivers and lakes, floods are an obvious outcome. This means a lot of people spend time anticipating the next torrential rainfall or flooding and always planning for the worst. What is needed: the mental-health equivalent of first aid.

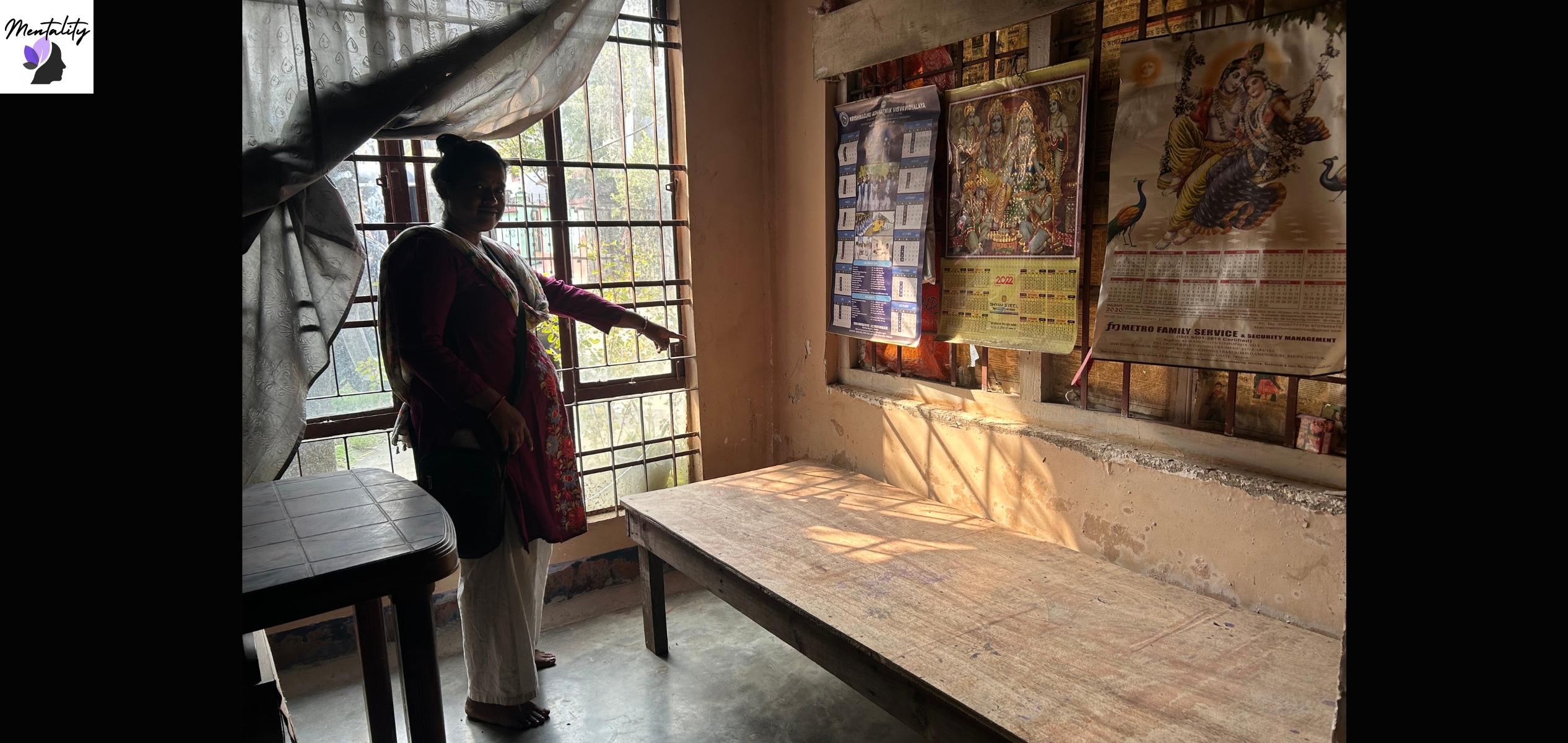

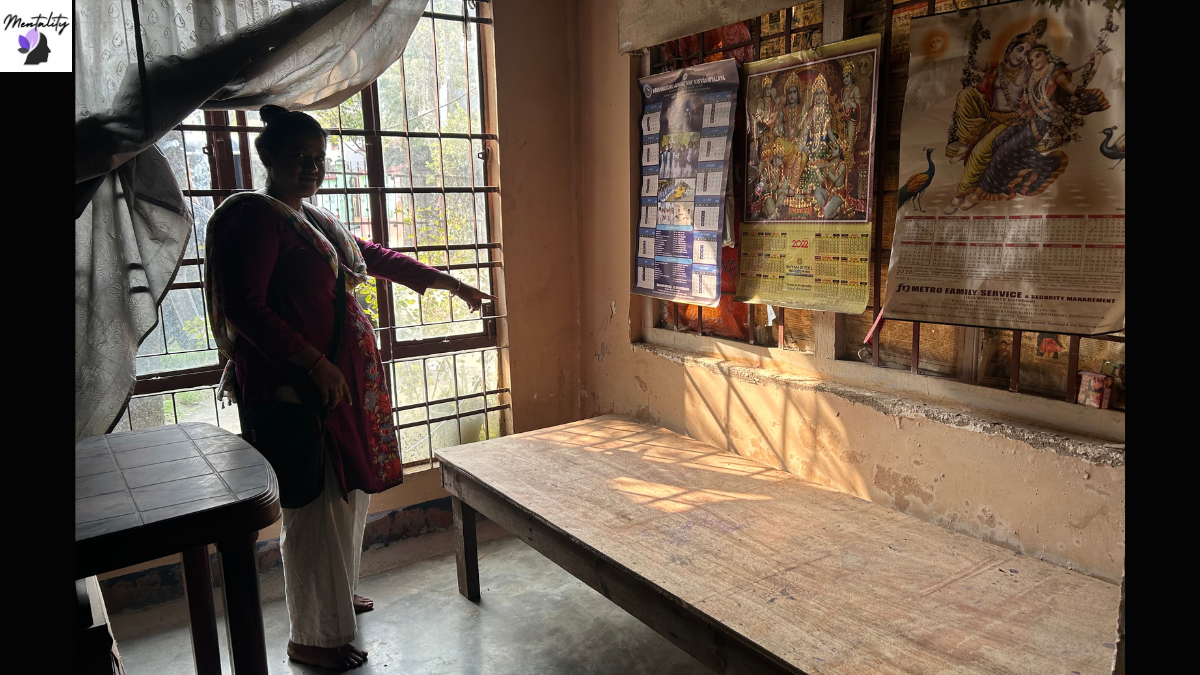

Even as dark clouds gathered over Guwahati, 36-year-old Rima Das, began rearranging her small one-room home. She pulled a large, blue plastic drum close to the bed, into which she put her daughter’s schoolbooks and certificates: the family’s most valuable possessions.

When it rains, Das knows that there is no time to rescue everything, other than what she can hold above her head.

In late August 2025, Guwahati, the capital city of Assam, experienced severe flooding due to heavy torrential rainfall. The intense downpours submerged all the major roads and residential areas, causing massive traffic jams and bringing normal life to a halt across the city.

But some neighbourhoods like Das’ were particularly badly affected. Das lives with her husband and 14-year-old daughter near Guwahati Shillong Road, popularly known as GS road, just a few steps from the Bharalu river. Even a single night of steady rain turns their lane into a waist-deep channel of dirty water.

Das works as a domestic worker in a few homes nearby. When she returned home in August this year, she saw her daughter’s book floating after flood waters had entered her home. “That sight left me trembling,” she said, “which was followed by palpitations, anxiety, and even fever.”

Bodies of disaster survivors, particularly in flood situations in Assam, enter a heightened state of stress, much like the classic fight, flight, or freeze response, said Dr Mythili Hazarika, Associate Professor of Clinical Psychology at Gauhati Medical College and Hospital. “In those moments, the amygdala takes over and the frontal lobe, which helps us think clearly, goes offline.”

Das admitted that her body sometimes reacts before she can understand what is happening.

“That’s why people may not be able to act rationally during a disaster,” said Dr Hazarika. “We treat these reactions like medical emergencies, and what they need most urgently is ‘psychological first aid’, the mental-health equivalent of medical first aid.”

Assam floods almost every year, as the Brahmaputra, the widest river in India, naturally shifts its course. According to the latest Flood Hazard Zonation Atlas, between 50% to 80% areas of the state’s 10 districts were inundated between 1998 and 2023.

Expansion of Guwahati

As the largest city in North East India, Guwahati acts as a gateway to six states. It has one of the busiest airports and has emerged as the commercial capital of the region.

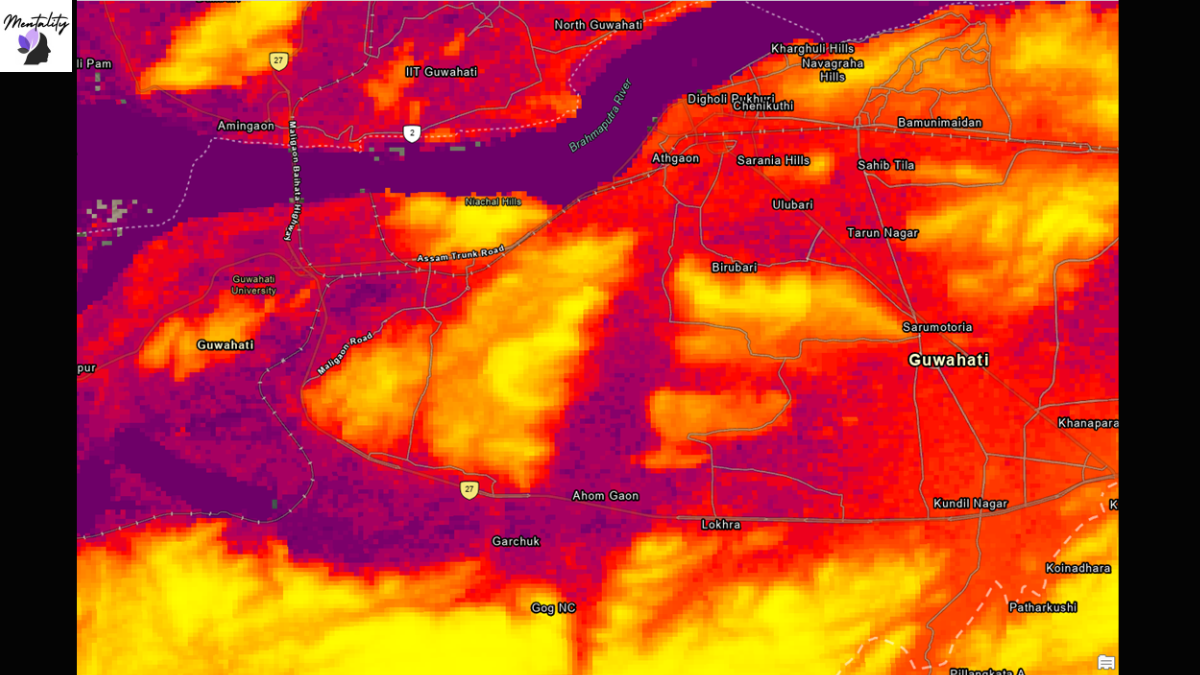

From 1.1 million people in 2020, its population is projected to hit 1.5 million inhabitants by 2035. The city inevitably expanded to places that were once natural catchments of the rivers and wetlands. “Stormwater has nowhere to go,” said Vikramjit Kakati, Professor and Director, Research & Development Cell, Assam Don Bosco University, who has mapped the city’s hydrology through a Digital Elevation Model (DEM).

A Digital Elevation Model (DEM) is a spatial representation of the earth’s surface that depicts terrain elevation using remote-sensing data from satellite imagery or aerial surveys, where elevation values are extracted, processed, and converted into a gridded digital surface.

Kakati’s model shows that large parts of the city such as GS Road, Maligaon, Lokhra, Birubari, downtown and sections of Zoo Road sit in low-lying areas almost at the same elevation as the Brahmaputra. “Stormwater rushes down faster, drains clog faster, and streets turn into rivers within minutes,” he said. What makes matters worse is Guwahati sits in a deep valley between hills.

Das migrated to Guwahati from Baksha, a small town in the Bodoland Territorial Region, 16 years ago when the city was smaller. While she understood that the city has expanded to take in more people like her who come in looking for better income, she said she lives in anxiety over erratic rainfall taking away the very job that brought her to the city. “I can’t go to work when there is waist-deep water,” she said.

For the last few years, Das admitted to being in a constant state of anxiety. “My daughter has even made a habit of sleeping with her school bag close to her pillow,” she said.

Rain brings anxiety

Rainfall was once limited to the monsoon season. But, in recent years, it has been sudden, violent, and often at unexpected times of the year. The rhythm of the city’s climate is broken, and with it, people’s sense of control.

Assam Government’s plan to develop a State Capital Region (SCR) by incorporating Guwahati and its adjoining regions resulted in crores of rupees of investment in the region. Assam State Capital Region Development Authority was formed as a nodal platform of the different governing agencies operating within the proposed SCR area.

On paper, ASCRDA’s objectives align with Guwahati Master Plan 2025, which puts a lot of emphasis on sustainability. But in reality things have been very different.

77-year-old retired physician, Dr Mridul Khaund is a Guwahati native. In many ways, the city has grown along with him. “Earlier, monsoon meant happiness,” he said. “Now it means danger.”

His home in Rukmini Nagar was flooded every year in the last four years, filling up the ground floor with water up to four feet. “Home doesn’t feel safe anymore,” he said.

Like Rima Das, Dr Khaund also anticipates a calamity long before it happens.

Dr Anant Bhan, who works on public health ethics, said this is called “anticipatory anxiety.”

For Das such anxiety is an annual affair. Last August, when rainfall would not let up, she remembered standing in her dark house, knee-deep in the water, holding a torch, while her daughter would not stop crying. “Even today, when I hear thunder, my heart starts racing.”

Seasonal impact on mental health depends on many things, said Bhan. “During the monsoon season, this can manifest in anxiety, mood disturbances, and unease,” he said. “Lack of sunlight as well as the need to stay indoors could also have an impact”.

For Dr Khaund, it is sleeplessness. Since his wife has a heart condition, he stays up thinking about what he would do if she needs help, he said. “How will I take her to the hospital in the rain?” he wondered.

Weak Response

Assam State Disaster Management Authority (ASDMA) works all year round, said Mirza Mahammad Irshad, Project Manager, Response & Recovery. “Water rolls down the hills around Guwahati along with sediments, faster than before,” he said. “As a result, the old drainage system has failed. We identified 615 such watershed points, which is why the city feels flooded even in moderate rain,” he said.

But Dr Hazarika said mental health support should be desperately included into the disaster management efforts. “Engineering fixes alone will not be enough.”

“What Guwahati needs now is mental-health infrastructure that understands the distress related to climate change like community counsellors, climate-anxiety workshops in schools, crisis support for elderly residents, and psychological first-aid training for responders,” she added.

Dr Hazarika headed ASDMA’s psychosocial tele-counselling service, Manojna, which aimed to provide psychological support to those affected. The initiative started and ended in 2021.

Das said she needs to be strong for her daughter. But, many times, just as she cannot control the rapid expansion of the city, she said she cannot control her anxieties.

Author: Chandrani Sinha

Chandrani is an award‑winning multimedia journalist from Guwahati, India with work in outlets like The Third Pole, Washington Post, and Climate Home.